As institutional interest in Bitcoin continues to deepen, one analogy dominates the narrative: Bitcoin as digital gold. Its scarcity, decentralized issuance, and resistance to inflation position it as a modern store of value in a digital age.

But Bitcoin doesn’t just share traits with gold — in many ways, its economic engine more closely resembles oil. Both Bitcoin mining and oil production rely on large-scale infrastructure, energy integration, and operational efficiency to extract value.

In this article, we’ll explore how Bitcoin compares to gold and oil as a commodity, the parallels between miners in each domain, and how hashrate — the computational power that fuels Bitcoin mining — is emerging as a new, tradable digital commodity.

Digital Scarcity

Scarcity, in economic terms, refers to limited availability relative to demand. But not all scarcity is the same. There are two main types: absolute scarcity and relative scarcity. Absolute scarcity means that there is a hard, fixed limit to supply that cannot be exceeded under any circumstances. Bitcoin is a prime example, with a maximum cap of 21 million coins programmed into its code.

Relative scarcity, on the other hand, refers to resources that are limited by external factors such as extraction costs, technological capabilities, or regulatory barriers. Oil falls into this category. While technically abundant in some contexts, its availability is constrained by how difficult, expensive, or politically feasible it is to access and distribute it.

Bitcoin mimics gold’s scarcity model, it is programmed in such a way that only 21 million Bitcoins will ever exist. Oil is scarce in the sense that it is a limited natural resource, but it is not reliably scarce in an investment or monetary sense. Its supply responds to market prices and technology, unlike Bitcoin or gold, whose scarcity is more structural.

The Halving

The halving events — which reduce Bitcoin issuance every 210,000 blocks or approximately four years — act as a digital scarcity mechanism, making it increasingly difficult to mine new coins over time. There will be a total of 32 Bitcoin halvings. After that, no more new bitcoins will be minted, and the total supply will be capped at 21 million BTC. The last fraction of a bitcoin (the final Satoshi’s) will be mined over many years, with the final BTC likely mined by around 2140. After that miners will no longer earn new bitcoins from block rewards. Instead, they will rely entirely on transaction fees as their incentive to secure the network. This built-in scarcity schedule is one of the reasons Bitcoin is often referred to as "digital gold.

The Stock-to-Flow Ratio

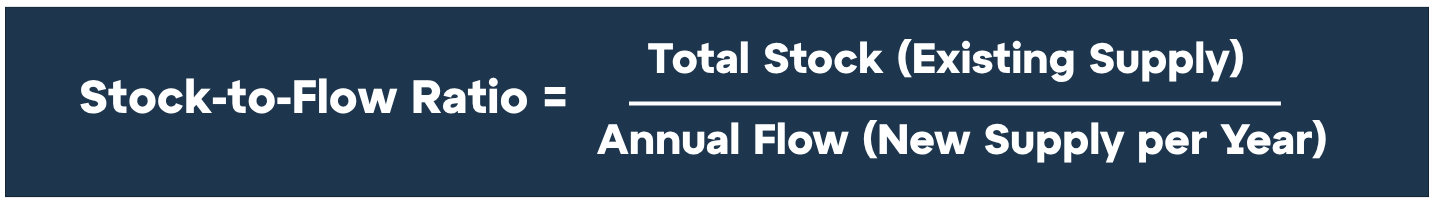

The stock-to-flow (S2F) model is a widely used framework for measuring the scarcity of commodities by comparing the existing supply (stock) to the annual production (flow). The higher the S2F ratio, the more scarce the asset is considered to be.

Gold has historically been viewed as a highly scarce asset, with an estimated above-ground stock of around 205,000 metric tons and an annual production of approximately 3,500 tons, resulting in a stock-to-flow ratio of about 59. This means it would take nearly six decades of current production levels to replenish the existing supply.

Bitcoin, by contrast, has a current supply of around 19.87 million coins. Following the April 2024 halving block subsidy is 3.125 BTC per block. Average blocktime is around 10 minutes which means current annual issuance is roughly 164,250 new coins (3.125 BTC x 144 blocks/day x 365 days). This gives Bitcoin a stock-to-flow ratio of approximately 121—more than double that of gold—positioning it as an even scarcer asset according to this model.

For comparison, oil has a very low stock-to-flow ratio, typically around 1.5, because its above-ground reserves are small relative to annual consumption. This low ratio reflects oil’s nature as a consumable commodity rather than a store of value.

94.63% of all Bitcoin is already mined (source: Timechain Calendar)

Bitcoin’s S2F ratio is unique in that it is programmed to increase over time due to its halving schedule, which cuts the block subsidy in half. With each halving, the flow component of the ratio decreases, which drives the S2F ratio higher and makes Bitcoin increasingly scarce. For instance, prior to the 2024 halving, the annual issuance was around 328,500 BTC (with a 6.25 BTC block reward), yielding an S2F ratio near 60—similar to gold. Post 2024 halving the S2F doubled to ~120.

At the next halving, expected in 2028, the reward will fall to 1.5625 BTC, and the annual supply will decrease to ~82,125 BTC, while the amount of BTC in circulation will be 20.343.750 pushing the S2F ratio to 247. This deliberate, algorithmic reduction in flow contrasts with the variable and price-sensitive production of traditional commodities like gold and oil, reinforcing Bitcoin’s appeal as a digital store of value engineered for increasing scarcity.

Digital Energy

Gold miners dig through tons of earth to extract small amounts of precious metal. Their profitability depends on ore grade, extraction costs, and the spot price of gold. Bitcoin miners operate in a digital realm, running machines that perform trillions of hashes per second to find the next block and earn a reward. While often compared to gold, Bitcoin production more closely resembles oil extraction. The parallels lie in three key areas: energy conversion, capital intensity, and operational efficiency. In this context, mining can be seen not just as digital extraction, but as programmable infrastructure, combining energy, hardware, and data systems into a new financial rail.

Energy Conversion: Bitcoin mining is essentially an energy-consuming process. Miners convert electricity into computational work to secure the network and create new Bitcoin. This makes Bitcoin fundamentally tied to energy economics, much like oil production, where natural resources are extracted, processed, and converted into usable energy products. Gold mining, in contrast, is primarily a physical extraction process focused on digging out ore; while it consumes energy, the value created is not directly linked to energy conversion in the same immediate, measurable way as Bitcoin or oil.

Capital Intensity: Both oil fields and Bitcoin mining farms require substantial upfront capital investment. For oil, this means drilling rigs, pipelines, refineries, and logistics infrastructure. For Bitcoin, it involves purchasing specialized mining hardware (ASICs) and building out data centres. Gold mining also requires capital but the scale and nature of infrastructure differ. Gold mines tend to be more tied to geological exploration and extraction, which can be less modular compared to setting up mining operations or oil wells.

Operational Efficiency and Margins: Profitability in oil and Bitcoin mining depends heavily on operational efficiency and managing ongoing costs, especially energy. Both industries face volatile commodity prices and must optimize for cost-per-unit output. For Bitcoin, that’s the cost per terahash of computing power; for oil, it’s the cost per barrel of extracted fuel. Gold mining, while subject to market prices and operational expenses, is less directly influenced by ongoing energy costs relative to the value generated.

These shared traits make Bitcoin mining a digital energy extraction industry. The economics of Bitcoin mining are fundamentally about converting and monetizing energy input, just as oil production is about extracting and monetizing energy resources.

Hashrate as a New Commodity

Just as oil is measured in barrels and gold in ounces, Bitcoin mining capacity is measured in hashrate, the total computational power securing the network. While often priced like a commodity, hashrate also represents a programmable layer of infrastructure, one that enables both sovereign-grade security and financial yield. Today, hashrate is becoming a commoditized input, complete with its own pricing, marketplaces, and financial instruments.

GoMining provides investors with access to hashrate through its flagship Alpha Blocks Fund, offering exposure to Bitcoin’s compute layer without the need to own or operate physical infrastructure. The fund is designed for qualified allocators seeking professionally managed access to Bitcoin’s foundational layer, with a strong emphasis on custody, governance, and operational transparency - positioning hashrate as a new class of digital commodity.

The implications are significant: hashrate can now be priced, leased, or tokenized. Institutional investors can allocate capital not just to Bitcoin itself, but also to hashrate derivatives and yield-generating mining funds. As hashrate markets evolve, infrastructure-focused platforms like GoMining continue to bridge the gap between raw compute power and institutional-grade access.

June 17, 2025